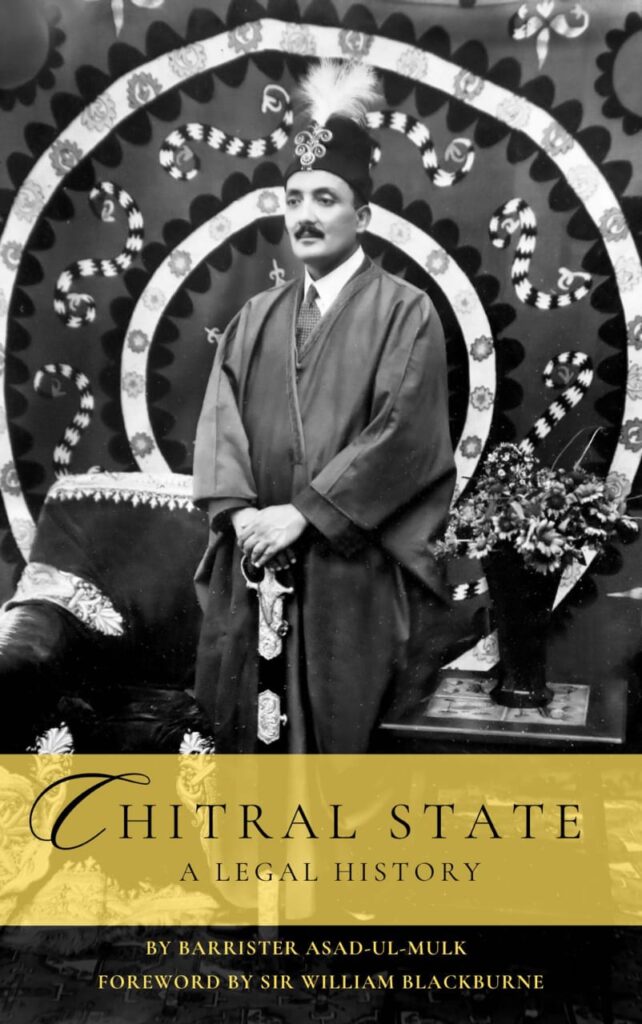

CHITRAL: A new book titled ‘Chitral State: A Legal History’ by Barrister Asad-ul-Mulk is scheduled to be launched soon. Unlike most books on Chitral which study history from a political, sociological, cultural or anthropological perspective, this new book studies the history of Chitral from a legal and jurisprudential perspective.

The author of the book is Barrister Asad-ul-Mulk who is a native of Chitral and has the distinction of being the first person from Chitral to be called to the Bar of England & Wales. Barrister Asad-ul-Mulk has studied at BPP Law School London and the Lincoln’s Inn (the same Inn from which Quaid-e-Azam was called to the Bar of England and Wales). Barrister Mulk happens to be the son of Shahzada Masood-ul-Mulk who has served as the CEO of the Sarhad Rural Support Programme (SRSP) for the last twenty-five years.

The foreword of the book has been written by Sir William Blackburne an eminent jurist who has remained a Judge at the Royal Courts of Justice in England for over twenty-five years. Sir William Blackburne is also a former Chairman of the Lincoln’s Inn, a former Chairman of the Pakistan Society in London and a former Vice-Chancellor of the County Palatine of Lancaster responsible for the administration of the estates belonging to the historic Duchy of Lancaster (a major source of His Majesty the King’s private income).

‘Chitral State: A Legal History’ seeks to trace the legal history of the territories forming the former State of Chitral from time immemorial. Building on the pre-state narrative, the book explores the emergence of the state over the region in the 14th century, and the steady development of a coercive court mechanism. The nature and facets of the legal hierarchy, and its monarchial character are subjected to scrutiny.

Since the customary laws of the State of Chitral were invariably never codified, a conscious attempt has been made in the book to document the customary laws of the region. The book sets out in detail the nature of a wide variety of laws, including; criminal, civil, property, personal, taxation and administrative law. The customary laws documented also expound upon the reciprocal obligations of the state and the individual. The contents of the customary laws have been gathered from hundreds of distinct and verifiable sources, and elaborated. The book elucidates the operation of law in a stratified society that is feudal in character.

The jurisdiction of the indigenous Courts i.e. the Qazi Courts, the Mizan-e-Shariah, the Judicial Council and the Mehtar’s Court are explained. The enforcement mechanism through which the judgments of the indigenous Courts were implemented is also explained in detail with reference to ancient edicts, royal decrees and proclamations. The position of the Mehtar (Ruler) as well as that of other state functionaries (judicial and quasi-judicial), as recognized by the legal system, becomes the subject of lengthy discourse in the book.

The evolution of the legal system, over the centuries, also constitutes the subject matter of the thesis. British influence, following the 19th century, is analyzed and investigated. And as a corollary, the concepts of sovereignty, suzerainty, subsidiary alliance and paramountcy come under jurisprudential discussion.

The book painstakingly reproduces all the important treaties executed between the State of Chitral and the British Crown. Also reproduced are many important letters and correspondence between the Mehtar of Chitral and the Viceroy of India, the Commander-in-Chief of the British Indian Army, the Secretary of State of India, the Governor and Chief Commissioner of the North West Frontier Province. Furthermore, important correspondence between the Mehtar of Chitral and the Rulers of other princely states and the Quaid-e-Azam also find feature. The vast majority of the documented letters and correspondence reproduced in this book have never been published before, and they cast light on the internal working of the State of Chitral including its legal system.

Events of momentous legal and territorial significance for the State of Chitral such as the severance of Mastuj (including Yarkhun and Kuh) and Laspur on the North-Western side and Ghizar, Yasin and Ishkoman on the North-Eastern side from the State of Chitral are studied. Similarly, the severance of Narsat, Bashgal and Dokalam on the Southern side also come under discussion. The reversion of Mastuj in 1914 and the agreement on which that reversion is founded are reproduced and explained. The status of the dependency of Kalam and its relation to the State of Chitral are pondered over, as are the limits of the boundary of the State of Dir. The legal instruments and treaties effecting severance and reversion are all reproduced in verbatim and subjected to jurisprudential scrutiny.

In depth chronology of events surrounding all successions to the Rulership of the State of Chitral since the mid-19th century are provided in the book. The transcripts of many of the speeches delivered on such occasions are also provided in the book.

The formation and functions of the Chitral State Bodyguard Force and the Chitral Scouts are traced and explained. The relationship of the State of Chitral with the State of Kashmir and the Emirate of Afghanistan is subjected to a prolonged critique.

Finally, the book proceeds to discuss the legal mechanism under the ‘Indian Independence Act, 1947’ that brought about the lapse of paramountcy, and eventually resulted in the accession of the State of Chitral to the Dominion of Pakistan in 1948. The book reproduces and discusses the constitutional significance of a plethora of documents including the Instrument of Accession of the State of Chitral.The book is spread over 530 pages and will shortly be available with Vanguard Books and other retailers. .. CN report, 14 Feb 2025